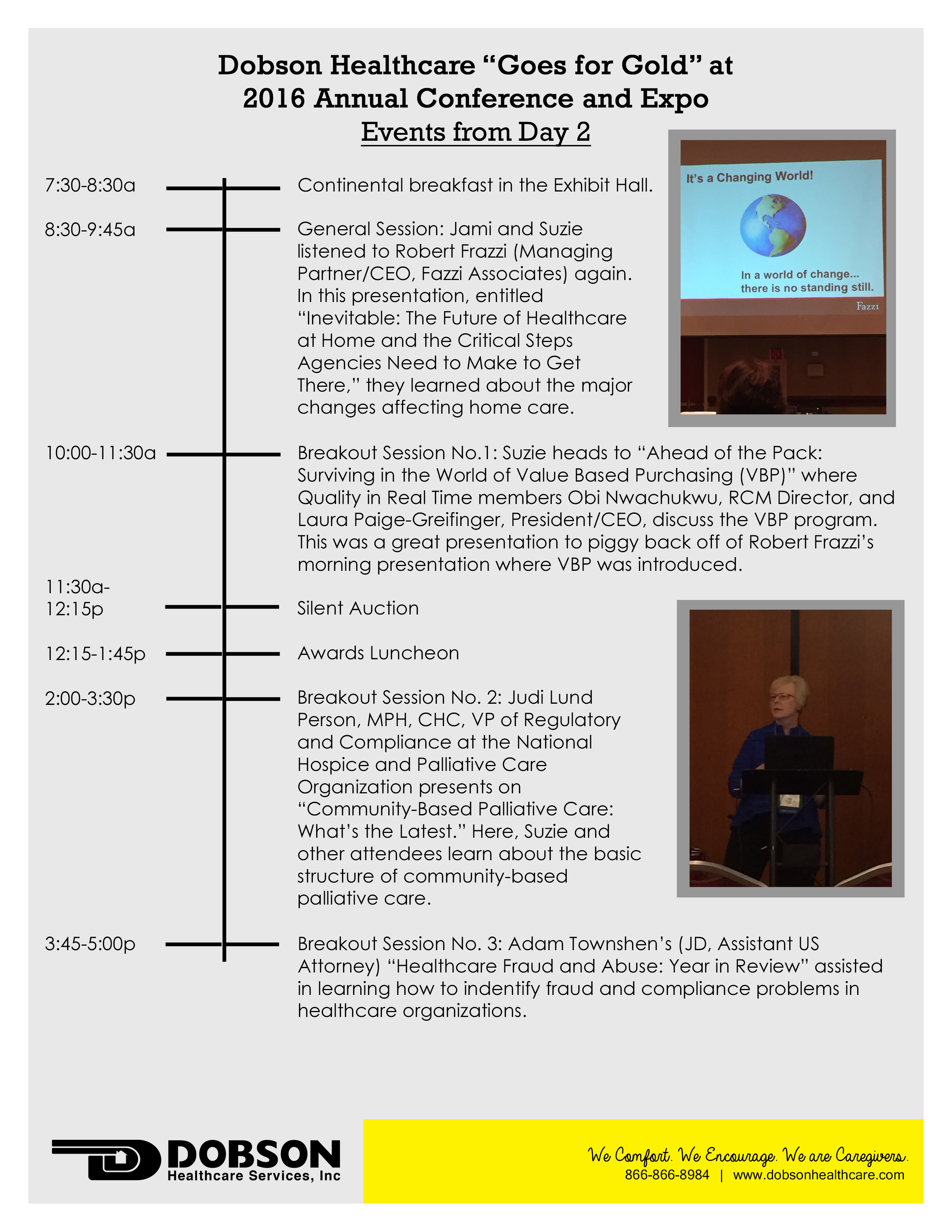

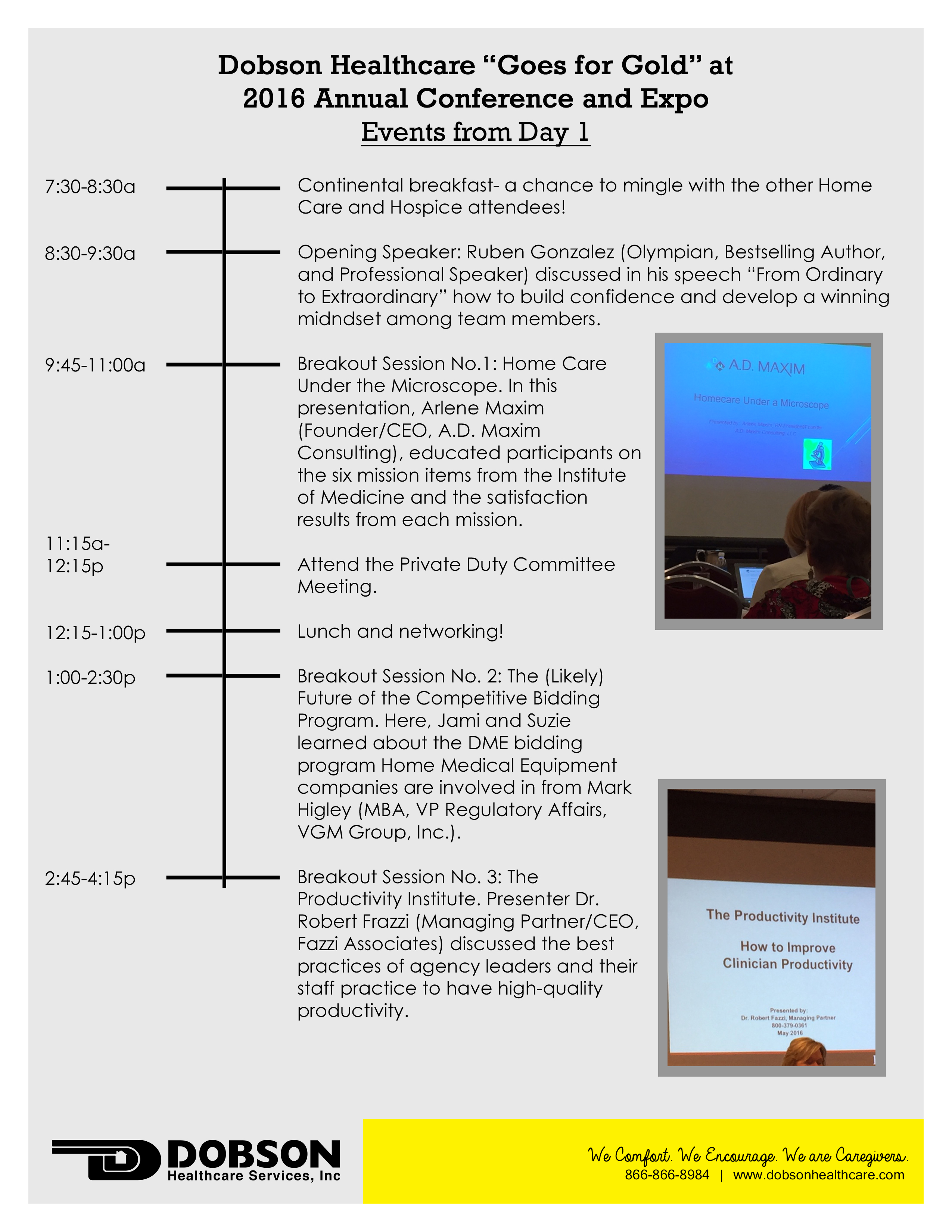

It’s day two for Jami (President and Founder) and Suzie (Corporate Director of Clinical Services) at this year’s Annual Education and Conference Expo hosted by the Michigan Association for Home Care and the Hospice and Palliative Care Association of Michigan. It was quite a full day for the pair, read about it below!

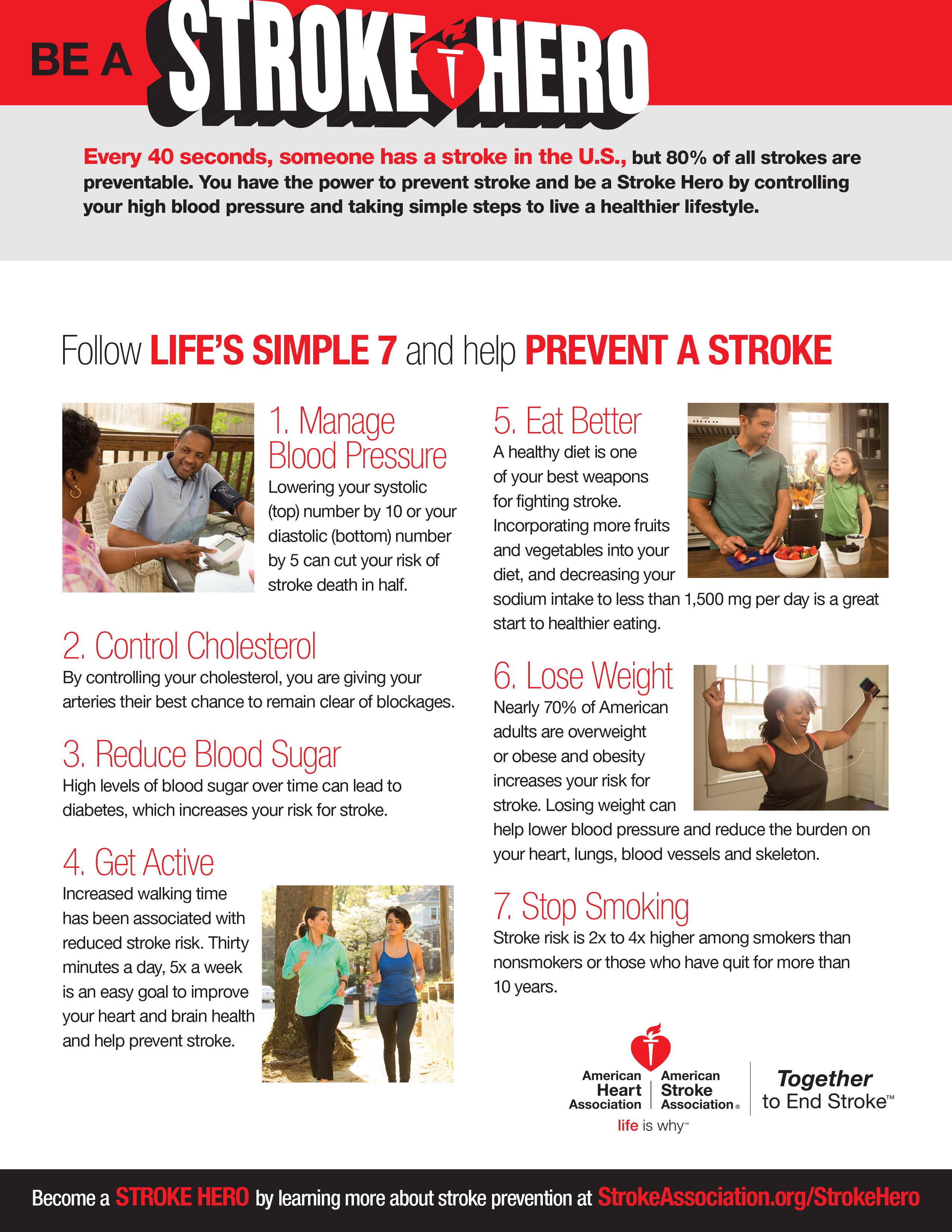

Because every 4 minutes someone dies from a stroke in the U.S, we are encouraging you to recognize you have the power to prevent stroke. Use Life’s Simple 7 tips to help teach your loved ones on healthy lifestyle steps they can take to prevent a stroke.

Members of our leadership team are attending this year’s Annual Education Conference and Expo! This event is jointly hosted by the Michigan Association for Home Care and the Hospice and Palliative Care Association of Michigan. Jami Dobson, President and Founder, and Suzie Pierce, Director of Clinical Services, are spending three days meeting with other professionals in Home Health, Hospice, Private Duty Care, and Palliative Care as well as Home Medical Equipment suppliers and Infusion specialist. They will also get a chance to listen to many educational presentations during the day and visit with vendors and exhibitors in the evening.

This year’s Conference theme is “Go for Gold” and focuses on encouraging team collaboration to be successful. Here’s a look at Jami and Suzie’s first day of the Conference!

The American Stroke Association states that

In the United States, someone has a stroke every 40 seconds.

When someone suffers a stroke, the effects can range from vision and speech problems to behavioral changes and paralysis. The extent of the damage done by a stroke depends on the location of the obstructions (such as the left side or right side of the brain or the brain stem) as well as how much brain tissues was affected.

Join us at Dobson Healthcare along with the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association and Stroke Heroes around the nation in the effort to put an end to stroke.

Please read through the “5 Things Every Stoke Hero Should Know” infographic and share it with your loved ones. Sharing could possibly save a life, even yours!

American Heart/Stroke Association (2016). “5 Things to Know About Stroke.” Retrived May 12, 2016 from http://www.strokeassociation.org/STROKEORG/AboutStroke/AmericanStrokeMonth/5ThingstoKnowAboutStroke/5-Things-to-Know-About-Stroke_UCM_463277_Article.jsp#.VzSfufkrKUm

American Heart/Stroke Association (2012, October, 23). “Effects of a Stroke.” Retrieved May 12, 2016 from http://www.strokeassociation.org/STROKEORG/AboutStroke/EffectsofStroke/Effects-of-Stroke_UCM_308534_SubHomePage.jsp

The reason we celebrate our nurses this week (May 6-12) and the advances the healthcare industry has made all boils down to one individual: Florence Nightingale. Today marks the 196th birthday of the woman known as the founder of modern nursing. Her courageous efforts, passion for assisting those in need, and no nonsense attitude laid the foundation of the nursing field as well as changed the outlook on nursing forever. The following article from Biography.com was published to educate the public on the pioneers life.

Early Life

Florence Nightingale was born on May 12, 1820, in Florence, Italy. She was the younger of two children. Nightingale’s affluent British family belonged to elite social circles. Her mother, Frances Nightingale, hailed from a family of merchants and took pride in socializing with people of prominent social standing. Despite her mother’s interest in social climbing, Florence herself was reportedly awkward in social situations. She preferred to avoid being the center of attention whenever possible. Strong-willed, Florence often butted heads with her mother, whom she viewed as overly controlling. Still, like many daughters, she was eager to please her mother. “I think I am got something more good-natured and complying,” Florence wrote in her own defense, concerning the mother-daughter relationship.

Florence’s father was William Shore Nightingale, a wealthy landowner who had inherited two estates—one at Lea Hurst, Derbyshire, and the other in Hampshire, Embley Park—when Florence was 5 years old. Florence was raised on the family estate at Lea Hurst, where her father provided her with a classical education, including studies in German, French and Italian.

by Henry Hering, copied by Elliott & Fry, half-plate glass copy negative, 1858 (1950s)

From a very young age, Florence Nightingale was active in philanthropy, ministering to the ill and poor people in the village neighboring her family’s estate. By the time she was 16 years old, it was clear to her that nursing was her calling. She believed it to be her divine purpose.

When Nightingale approached her parents and told them about her ambitions to become a nurse, they were not pleased. In fact, her parents forbade her to pursue nursing. During the Victorian Era, a young lady of Nightingale’s social stature was expected to marry a man of means—not take up a job that was viewed as lowly menial labor by the upper social classes. When Nightingale was 17 years old, she refused a marriage proposal from a “suitable” gentleman, Richard Monckton Milnes.

Nightingale explained her reason for turning him down, saying that while he stimulated her intellectually and romantically, her “moral…active nature…requires satisfaction, and that would not find it in this life.” Determined to pursue her true calling despite her parents’ objections, in 1844, Nightingale enrolled as a nursing student at the Lutheran Hospital of Pastor Fliedner in Kaiserswerth, Germany.

Crimean War

In the early 1850s, Nightingale returned to London, where she took a nursing job in a Middlesex hospital for ailing governesses. Her performance there so impressed her employer that Nightingale was promoted to superintendant within just a year of being hired. The position proved challenging as Nightingale grappled with a cholera outbreak and unsanitary conditions conducive to the rapid spread of the disease. Nightingale made it her mission to improve hygiene practices, significantly lowering the death rate at the hospital in the process. The hard work took a toll on her health. She had just barely recovered when the biggest challenge of her nursing career presented itself.

In October of 1853, the Crimean War broke out. The British Empire was at war against the Russian Empire for control of the Ottoman Empire. Thousands of British soldiers were sent to the Black Sea, where supplies quickly dwindled. By 1854, no fewer than 18,000 soldiers had been admitted into military hospitals.

At the time, there were no female nurses stationed at hospitals in the Crimea. The poor reputation of past female nurses had led the war office to avoid hiring more. But, after the Battle of Alma, England was in an uproar about the neglect of their ill and injured soldiers, who not only lacked sufficient medical attention due to hospitals being horribly understaffed, but also languished in appallingly unsanitary and inhumane conditions.

Pioneering Nurse

In late 1854, Nightingale received a letter from Secretary of War Sidney Herbert, asking her to organize a corps of nurses to tend to the sick and fallen soldiers in the Crimea. Nightingale rose to her calling. She quickly assembled a team of 34 nurses from a variety of religious orders, and sailed with them to the Crimea just a few days later.

Although they had been warned of the horrid conditions there, nothing could have prepared Nightingale and her nurses for what they saw when they arrived at Scutari, the British base hospital in Constantinople. The hospital sat on top of a large cesspool, which contaminated the water and the hospital building itself. Patients lay on in their own excrement on stretchers strewn throughout  the hallways. Rodents and bugs scurried past them. The most basic supplies, such as bandages and soap, grew increasingly scarce as the number of ill and wounded steadily increased. Even water needed to be rationed. More soldiers were dying from infectious diseases like typhoid and cholera than from injuries incurred in battle.

the hallways. Rodents and bugs scurried past them. The most basic supplies, such as bandages and soap, grew increasingly scarce as the number of ill and wounded steadily increased. Even water needed to be rationed. More soldiers were dying from infectious diseases like typhoid and cholera than from injuries incurred in battle.

The no-nonsense Nightingale quickly set to work. She procured hundreds of scrub brushes and asked the least infirm patients to scrub the inside of the hospital from floor to ceiling. Nightingale herself spent every waking minute caring for the soldiers. In the evenings she moved through the dark hallways carrying a lamp while making her rounds, ministering to patient after patient. The soldiers, who were both moved and comforted by her endless supply of compassion, took to calling her “the Lady with the Lamp.” Others simply called her “the Angel of the Crimea.” Her work reduced the hospital’s death rate by two-thirds.

In additional to vastly improving the sanitary conditions of the hospital, Nightingale created a number of patient services that contributed to improving the quality of their hospital stay. She instituted the creation of an “invalid’s kitchen” where appealing food for patients with special dietary requirements was cooked. She established a laundry so that patients would have clean linens. She also instituted a classroom and a library, for patients’ intellectual stimulation and entertainment.

Recognition and Appreciation

Based on her observations in the Crimea, Nightingale wrote Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency and Hospital Administration of the British Army, an 830-page report analyzing her experience and proposing reforms for other military hospitals operating under poor conditions. The book would spark a total restructuring of the War Office’s administrative department, including the establishment of a Royal Commission for the Health of the Army in 1857.

Nightingale remained at Scutari for a year and a half. She left in the summer of 1856, once the Crimean conflict was resolved, and returned to her childhood home at Lea Hurst. To her surprise she was met with a hero’s welcome, which the humble nurse did her best to avoid. The Queen rewarded Nightingale’s work by presenting her with an engraved brooch that came to be known as the “Nightingale Jewel” and by granting her a prize of $250,000 from the British government.

Nightingale decided to use the money to further her cause. In 1860, she funded the establishment of St. Thomas’ Hospital, and within it, the Nightingale Training School for Nurses. Nightingale became a figure of public admiration. Poems, songs and plays were written and dedicated in the heroine’s honor. Young women aspired to be like her. Eager to follow her example, even women from the wealthy upper classes started enrolling at the training school. Thanks to Nightingale, nursing was no longer frowned upon by the upper classes; it had, in fact, come to be viewed as an honorable vocation.

Later Life

While at Sc utari, Nightingale had contracted “Crimean fever” and would never fully recover. By the time she was 38 years old, she was homebound and bedridden, and would be so for the remainder of her life. Fiercely determined, and dedicated as ever to improving health care and alleviating patients’ suffering, Nightingale continued her work from her bed.

utari, Nightingale had contracted “Crimean fever” and would never fully recover. By the time she was 38 years old, she was homebound and bedridden, and would be so for the remainder of her life. Fiercely determined, and dedicated as ever to improving health care and alleviating patients’ suffering, Nightingale continued her work from her bed.

Residing in Mayfair, she remained an authority and advocate of health care reform, interviewing politicians and welcoming distinguished visitors from her bed. In 1859, she published Notes on Hospitals, which focused on how to properly run civilian hospitals.

Throughout the U.S. Civil War, she was frequently consulted about how to best manage field hospitals. Nightingale also served as an authority on public sanitation issues in India for both the military and civilians, although she had never been to India herself. In 1908, at the age of 88, she was conferred the merit of honor by King Edward. In May of 1910, she received a congratulatory message from King George on her 90th birthday.

Death and Legacy

In August 1910, Florence Nightingale fell ill, but seemed to recover and was reportedly in good spirits. A week later, on the evening of Friday, August 12, 1910, she developed an array of troubling symptoms. She died unexpectedly at 2 pm the following day, Saturday, August 13, at her home in London.

Characteristically, she had expressed the desire that her funeral be a quiet and modest affair, despite the public’s desire to honor Nightingale—who tirelessly devoted her life to preventing disease and ensuring safe and compassionate treatment for the poor and the suffering. Respecting her last wishes, her relatives turned down a national funeral. The “Lady with the Lamp” was laid to rest in her family’s plot at St. Margaret’s Church, East Wellow, in Hampshire, England.

The Florence Nightingale Museum, which sits at the site of the original Nightingale Training School for Nurses, houses more than 2,000 artifacts commemorating the life and career of the “Angel of the Crimea.” To this day, Florence Nightingale is broadly acknowledged and revered as the pioneer of modern nursing.

Biography.com Editors (n.d.) “Florence Nightingale Biography.” Retrieved May 9, 2016 from www.biography.com/people/florence-nightingale-9423539

Today our Director of Operations, Jenna Schrumpf, is in Lansing to meet with fellow brain injury advocates and legislative leaders. We invite you to follow along her day in our Capitol Day interactive timeline!

V. Joe (2012, October 16). “A Guide to Nursing Specialties.” Retrieved on May 9, 2016 from http://allnurses.com/nurses-rock/a-guide-to-792385.html

We come into contact with germs every day. According¹ to Philip Tierno, Director of Clinical Microbiology and Immunology at NYU and author of “The Secret Life of Germs,” 60,000 types of germs to be exact. They are on gas pumps, shopping carts, cell phones, elevator buttons, and the list goes on. Being in the healthcare industry, it is not only important for our staff to practice proper hand hygiene before assisting our clients but it is also important that we share these techniques to the public to help prevent the spread of infections and diseases. Below you will find tips to improve your hand hygiene techniques.

First, what exactly is Hand Hygiene?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)²,

“Hand Hygiene means cleaning your hands by using either handwashing (washing hands with soap and water), antiseptic hand wash, antiseptic hand rub (i.e. alcohol-based hand sanitizer including foam or gel), or surgical hand antisepsis.”

When should you perform Hand Hygiene?

The CDC suggests you should clean your hands4:

- Before eating

- Before and after having direct contact with a patient’s intact skin (taking a pulse or blood pressure, performing physical examinations, lifting the patient in bed)

- After contact with blood, body fluids or excretions, mucous membranes, non-intact skin, or wound dressings

- After contact with inanimate objects (including medical equipment) in the immediate vicinity of the patient

- If hands will be moving from a contaminated-body site to a clean-body site during patient care

- After glove removal

- After using a restroom

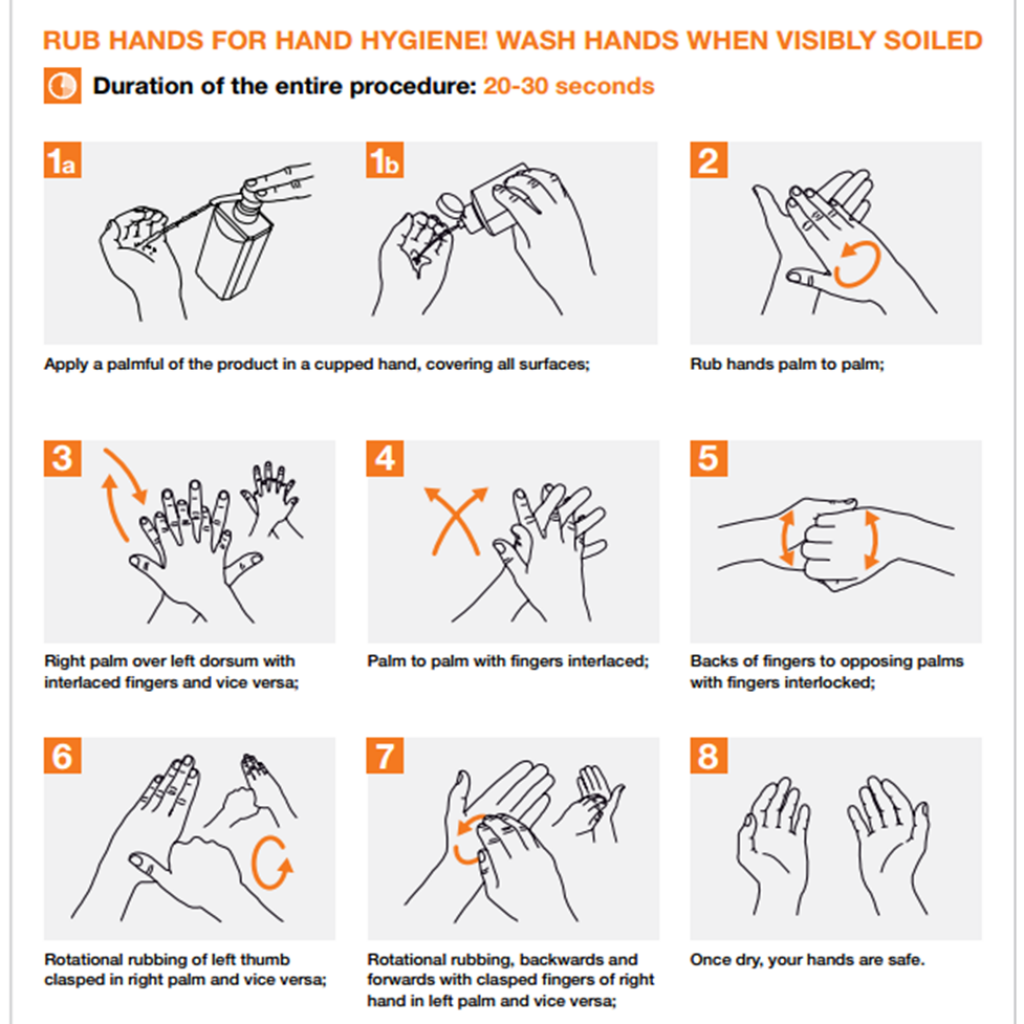

If you hands are not visibly dirty, cleaning your hands with an alcohol-based hand sanitizer is the preferred method. When your hands are visibly dirty with blood or other body fluids or after using the toilet, you should wash your hands with soap and water. With both methods, the duration of time for rubbing your hands clean is at least 15 seconds. The image below shows the technique for washing your hands. These hand motions can be applied to when using the hand sanitizer method as well as the soap and water method. Note: with the soap and water technique, you should dry your hands thoroughly with a towel and use that towel to turn off the faucet.

Figure 2: How to Hand Rub. “Hand Hygiene: Why, How & When?,” by World Health Organization, (2009).

What are the “My Five Moments for Hand Hygiene?”

The “My Five Moments for Hand Hygiene” were identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as five crucial moments when hand hygiene is required during the care of patients. Figure 2 includes illustrations of the My Five Moments for Hand Hygiene. According to the WHO³, the patient zone in a home care setting “…corresponds to the patient (his/her intact skin and clothes) and the home environment, which is contaminated mainly by the patient’s flora. Any care items and transportation containers brought by the [Health Care Worker] HCWs represent the health-care area. The point of care is where the procedure takes place.” Because there are various direct and indirect contact with the patient, proper hand hygiene is imperative.

Figure 2: Illustration of the My Five Moments for Hand Hygiene and zone concepts. “Hand Hygiene in Outpatient and Home-based Care and Long-term Care Facilities,” by World Health Organization, (2012).

Want to learn more?

For more resources on Hand Hygiene, visit the following sites:

http://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/providers/index.html

http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/en/

¹ Brownstein J., Chitale R. (2008, Spetember 5). “10 Germy Surfaces You Touch Every Day.” Retrieved May 2, 2016 from http://abcnews.go.com/Health/ColdandFluNews/story?id=5727571&page=1

² The Centers for Disease and Prevention. (2016, March 15). “Clean Hands Count for Healthcare Providers.” Retrieved May 2, 2016 from http://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/providers/index.html

³ World Health Organization (2012). “Hand Hygiene in Outpatient and Home-based Care and Long-term Care Facilities.” Retrieved May 2, 2016 from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/78060/1/9789241503372_eng.pdf?ua=1

4 World Health Organization (2009). “Hand Hygiene: Why, How & When?” Retrieved May 2, 2016 from http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Hand_Hygiene_Why_How_and_When_Brochure.pdf?ua=1

How much do you know about strokes? For all awareness levels, this is a great introductory video for National Stroke Awareness Month!

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/nxwu9z1bhU0″ frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen></iframe>

Source: National Stroke Association (2016, April 9). National Stroke Awareness Month: Are You StreetSmart About Stroke? Retrieved May 4, 2016 from www.stroke.org